|

As part of my recent USA trip I stopped off in New Haven, mainly to see one of Louis Kahn's best known buildings, the Yale University Art Gallery. Completed in 1953, it was the first to demonstrate his key architectural distinction between 'servant' and 'served' space. In other words Kahn aimed to create large uninterrupted volumes for occupation and use, in this case galleries for art, with staircases and other servicing elements distinguished by their place in the geometrically ordered plan but given their own distinct architectural treatment. The ceiling, emphasising the building's continuity of space, is a repetitive triangular grid derived structurally from the space frame, but heavy where the space frame is light. Kahn's aim here is to give a timeless, quasi-monumental quality to the building, which remains impressive but is less startling than it would have appeared in the 1950s, in contrast to the work of Mies and perhaps a complement to the contemporary work of Le Corbusier. It also relates to the more general concerns about materiality in the 1950s , widely known as Brutalism. The use of shuttered concrete, unclad brick and block work were unprecedented at that time for a public building in the USA and this material quality is still startling but architecturally effective.

65 Comments

I have recently returned from the USA, where I gave a lecture at MIT on the architectural photographer Eric de Mare, accompanying an exhibition currently showing (until April 8) in the Wolk Gallery in the MIT main building on Massachusetts Avenue. Nearby was some highly interesting modern architecture both at Harvard and MIT- Le Corbusier's Carpenter Center, Frank Gehry's Stata Center, and the highspot- seen on a day with sunshine and deep snow- Eero Saarinen's MIT Chapel completed in 1955 and which I scarcely knew.  Saarinen is not much discussed now, but was one of the leading architects in the USA in the 1950s, having emigrated from his native Finland to the USA as a teenager in 1923. It's clear he brought something of a Scandinavian sensibility with him- the undulating walls of rough brickwork for one thing- and the overall effect of this small windowless space is powerful and dramatic, with light coming down to the altar through the cascading sculpture of Harry Bertoia. There's something space-age about it too- and this reflects the preoccupations seen in his best-known works, the terminal at JFK Airport originally built for TWA and the great parabolic arch at St Louis.

Last week saw the In Place of Architecture Symposium at Nottingham Trent University. organised by Andy Lock and Fiona Maclaren- accompanying an exhibition (still on at the University's Bonington Gallery) of the work of a number of artist-photographers working with the theme. Several of them, including Peter Ainsworth, Guy Moreton and Esther Johnson presented their work at the Symposium, and one of the highlights was the work of Emily Richardson- her film of the modernist house of H. T. Cadbury-Brown- empty, abandoned, taken over by time, is an elegaic piece of power and subtlety. This very worthwhile event was hopefully the first of a series of explorations on the theme of artists working with architecture as their material. I was asked to give the Keynote speech, which was titled Image and Counter-Image: architecture and its narratives: it dealt with the dominant narrative of photographing architectural form, and counterpointed that with some alternative readings of architecture and its imaging. Nigel Henderson's work, as ever, went down very well. And an extended discussion of the photography of the Barcelona Pavilion was enlivened by the image of Carolyn Butterworth licking the Pavilion, a critique of architecture and its photography on several levels.

There's a lot of recent architecture in Japan that has been highly interesting to those in the West- and the idea that Japan had developed its own version of Modernism has been around since (at least) Kenzo Tange's work in the 1960s. While the combination of a sense of the austerity and compositional clarity of Japanese traditional architecture has been seen as a forerunner of modernist concerns for a much longer period- Frank Lloyd Wright and Walter Gropius were both suitably inspired, and wrote on the subject. The work of Tadao Ando can be seen extensively in Japan, particularly in the area of Kansai around his home city of Osaka. His work is often described, not least by him, as translating a Japanese sense of space, or perhaps more accurately a Japanese existentialism, into modern materiality and abstract geometry. Certain smaller projects, such as the Lotus Temple on Awaji Island, are highly inventive in their design and very powerful in their effect. Others, such as the nearby Yumebutai development and park, seem to be a repetition of themes he's done better elsewhere. Kengo Kuma, even though he is also well known and has also worked in Europe, is not necessarily as well regarded. But the Nezu Museum in Tokyo, set in a garden-oasis in the fashionable district of Aoyama, is delightful. It seems to be a less ponderous version, literally and figuratively, of a current interpretation of Japanese-ness, simple and understated, connecting with that tradition quite directly.

I have just returned from a first trip to Japan, a trip full of architecture as well as much else- and this will form the basis for several blog posts. This first post puts together two buildings 'made' in London, but built in Japan. The Nagakin Capsule tower was designed by Kisho Kurokawa and finished in 1972: it provided the most minimal of dwelling standards in its capsule flats, and now stands derelict in an area of Tokyo full of new development. In clear emulation of Archigram projects done a decade earlier- Peter Cook's Plug-In City would have consisted of such prefabricated pods suspended from a service network, as Kurokawa's building does. But even closer is Warren Chalk's design for a Capsule Tower, done in 1965. However influential Archigram's work was, this is among the closest realisations of its principles- and now soon to disappear. The second building originating in conversations in London is Foreign Office Architects' Yokohama Port Terminal building, completed in 2002. Farshid Moussavi and Alejandro Zaera-Polo, then young and untried, won the competition to build this major piece of urban infrastructure in 1995: then tutors at the Architectural Association in London, they had both worked for OMA. Heralded as both a new urban type- a cruise ship terminal interwoven with a public space, an extension of nearby parks- it also represented a new architectural vocabulary of form, an unparalelled urban topography. As Zaera-Polo has written: 'the project is generated from a circulation diagram that aspires to eliminate the linear structure characteristic of piers, and the directionality of the circulation.' In other words, a complex and flowing spatial model is adopted, changing direction and level, and enabled by the use of folded steel plates and concrete girders that minimise vertical support. Space seems to drift and fold, an exciting but not disorienting experience: some have said that the built project is disappointing compared to the radical nature of the spaces as drawn. While the project perhaps promised magic, the building does realise a powerful and effective new kind of architecturally determined public space.

The reconstructed Birmingham New Street station opened yesterday 20 September, almost exactly two years after the opening of the new Library of Birmingham. Unlike that major and acclaimed project by Mecanoo, however, the architect has been nowhere to be seen in the fairly extensive media coverage- Alejandro Zaera-Polo of Foreign Office Architects with his then partner Farshid Moussavi got the commission in 2007 but walked off the job when, among other changes, cost cutting led to the replacement of the concrete of the atrium interior with stretched fabric. However much of the original design remains, it's highly regrettable and short sighted that a bold and highly original design should have been so compromised: imagine if Network Rail's in-house architects had been given the commission in the first place ?

A shopping centre, part of the development and dominated by a large John Lewis store, is named Grand Central: New York Grand Central Station is clearly the model, but is a far more impressive space- and dominated by an Oyster Bar rather than yet another branch of Pret a Manger ! The exterior, largely reusing the existing concrete frame of the replaced building is animated by twists and turns of faceted stainless steel cladding. An island site in the heart of the city, it is surrounded by streets both major and minor, and the facade's dazzling reflections are successful in bringing something strange and futuristic to the nineteen and twentieth century context that surrounds it. The architectural photographer Simon Kennedy has an exhibition of his work opening this evening

1 September at the Fitzrovia Gallery 139 Whitfield St London W1T 5EN. I have written a text to accompany the images, part of which follows. The show runs until 12 September. The photographs seen in Constructed Images show Wolfson House in central London: formerly used as a laboratory, it is presented empty and unused. A building of everyday modernism, it was built at a time when architecture was built to an ideal, with the integrity of real materials and building elements rather than the simulacra of the post modern condition. Each photograph is a construction, a photomontage of images from divergent space and time, so the photographs demand careful scrutiny. There is a dislocation of elements to create new formal configurations: staircases that lead nowhere, windows that are fractured, a play of spaces that makes no sense. A faceted, fragmented montage of recognisable components, presented both in positive and negative images: and these elements are carefully juxtaposed and transformed into a new unity, reimagining modernist qualities. These constructed images are very much redolent of the analytical Cubism that influenced them, but also at a smaller scale echo the construction of architectural images by other contemporary artist-photographers such as Andreas Gursky or Beate Guetschow. These uninhabited spaces are re-made into new intriguing configurations, shaped by the utopian impulse of modernism. They present an intriguing play with time and circumstance to build an alternate photographic language of architecture. AA Files issue 70 has just been published, with a wealth of diverse material including texts about Robin Evans, Jan Kaplicky, Piano and Rogers and 'possible' Pompidou Centres, and Niemeyer's Copan building, among much else. There is an essay by me on the photography of Eric de Mare in relation to what was termed 'the Functional Tradition:' he travelled throughout Britain in the Summer of 1956 looking at old and completely forgotten industrial structures. This voyage of discovery of multifarious buildings including dock warehouses, mills, breweries, canal buildings and so on culminated in an Architectural Review article, and following that a book of the same name which appeared in 1958.

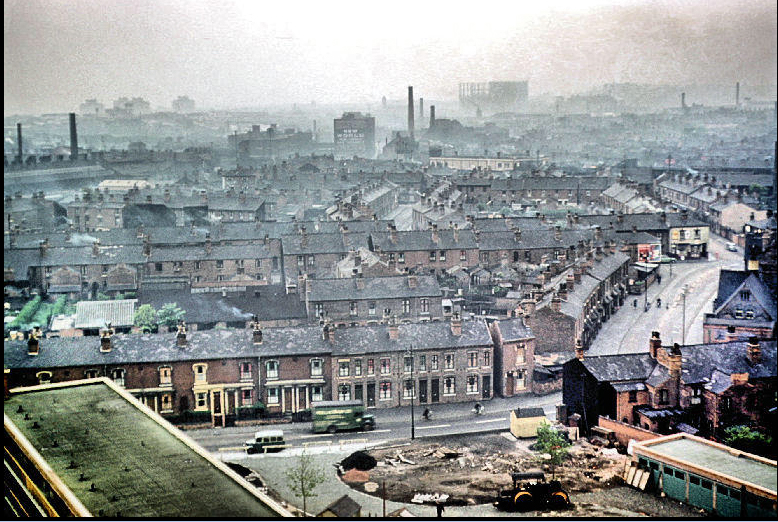

Although 'architecture without architects', to use Rudofsky's later phrase, there was much that was relevant to architects of that period, who saw these structures as expressing a refreshing originality of form not limited by traditional aesthetics. This essay narrates and interprets this body of work- which, incidentally, turned de Mare from being an architect-journalist to being a celebrated photographer- and, we hope, will also be later published in a far more comprehensive as a book. A tutor in Geography in the extra-mural department of Birmingham University, Phyllis Nicklin (1909-69) left behind for the University an extraordinary archive of 35mm slides that she had taken, to use in her classes, in the 1950s and 60s. Her subject was the city which she lived in all her life and her photographs documented the enormous changes in the city's appearance and physical fabric, as it underwent a process of transformation unprecedented in British cities. Many of the images show the nineteenth century fabric, typically of red brick terraces and small factories, juxtaposed with shockingly new modern forms: housing tower blocks, shiny office buildings, wide dual carriageway roads. Birmingham's urban renewal was going on apace. For many seeing Nicklin's pictures now, they evoke a nostalgia for simpler times of shared values and community. But however ordinary their purpose, that of a record and a teaching aid, the most compelling images picture a city in transition, in a world then filled with optimism about the modern and erasure of the outdated past. Many have an atmospheric quality, accentuated by their Kodachrome colour cast, and like the best documentary photographs transcend their matter-of-fact origin to have a significance far beyond their local context. This rich archive is the subject of a small interactive exhibition- Phyllis Nicklin Unseen- currently to be seen at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, set up by the website brumpic.com. A larger exhibition is planned, and see the archive of 446 scanned images on the Birmingham University website, at epapers.ac.uk/chrysalis.html.

My recent lecture to the AA was a reminder that many still don't know the great significance of the work of F R Yerbury in bringing modern architecture to Britain in the 1920s and early 30s. Before others whose names are now better-known, he photographed an electic collection of whatever buildings were new on his travels in Europe, almost by accident including Le Corbusier among a wealth of now forgotten figures. And he photographed the buildings of post-Revolutionary Russia as well as the American skyscrapers seen on a visit in 1926.

There's an exhibition of some of his photographs currently at the Architectural Association Photo Library Gallery, 37 Bedford Square London WC1, where his archive of several thousand negatives is held. |

Archives

September 2020

Categories

All

|